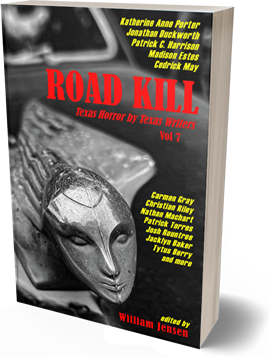

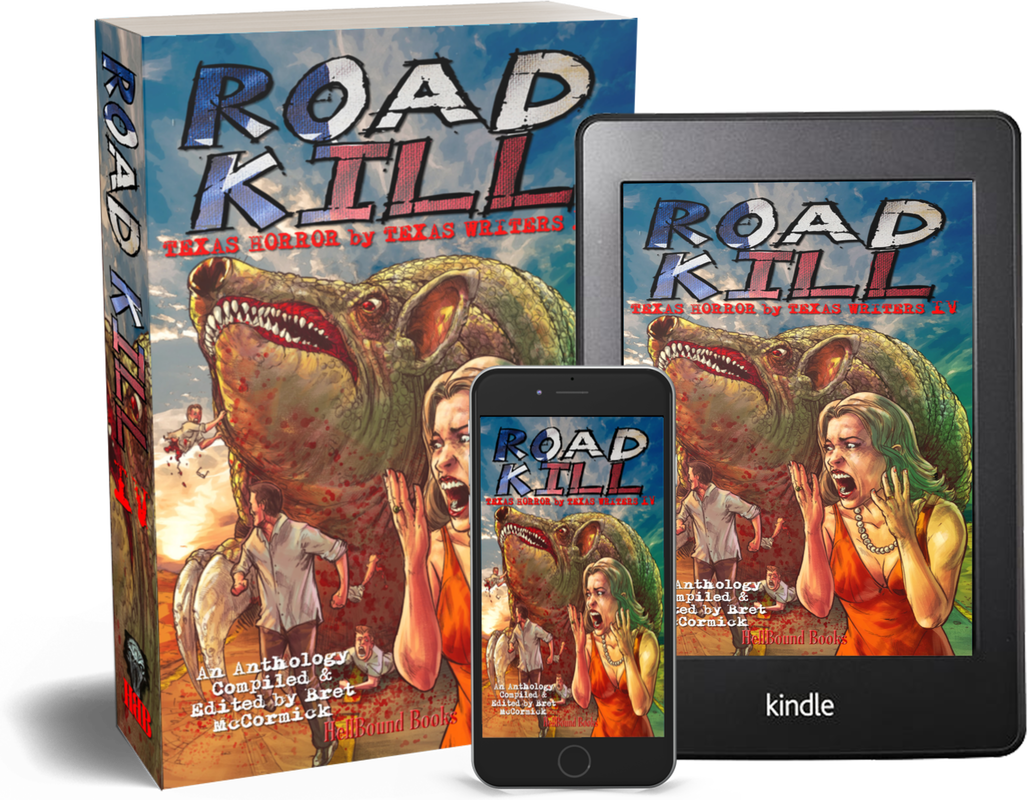

The anthology I've been editing for a while is now out and ready to scare you. Road Kill: Texas Horror by Texas Writers, vol. 7 features new and familiar names such as Patrick C. Harrison III, Madison Estes, Christian Riley, and Katherine Anne Porter. I hope to see people at readings and signings coming up in October and November. READINGS

October 6. 2:00--Center for the Study of the Southwest in Brazos Hall at Texas State University in San Marcos. October 11th. 6:00--Interabang Books in Dallas. October 18th. 5:00--The Twig Bookstore in San Antonio October 22nd. 3:00--Murder by the Book in Houston October 25th. (time TBD) Wild Detectives in Dallas November 2nd. 6:00--Sam Houston State University in Huntsville. November 12th. (time TBD)--Galveston Books in Galveston

0 Comments

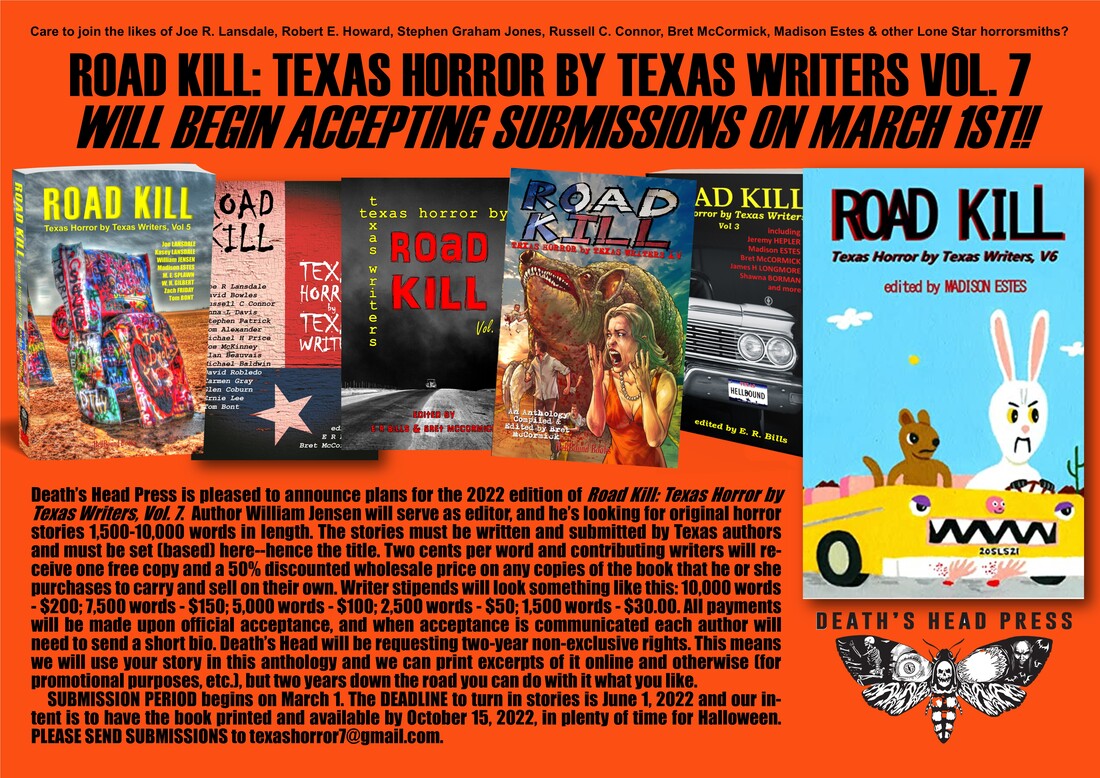

I am thrilled to be editing the upcoming anthology Road Kill: Texas Horror by Texas Writers vol. 7!

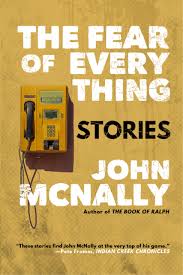

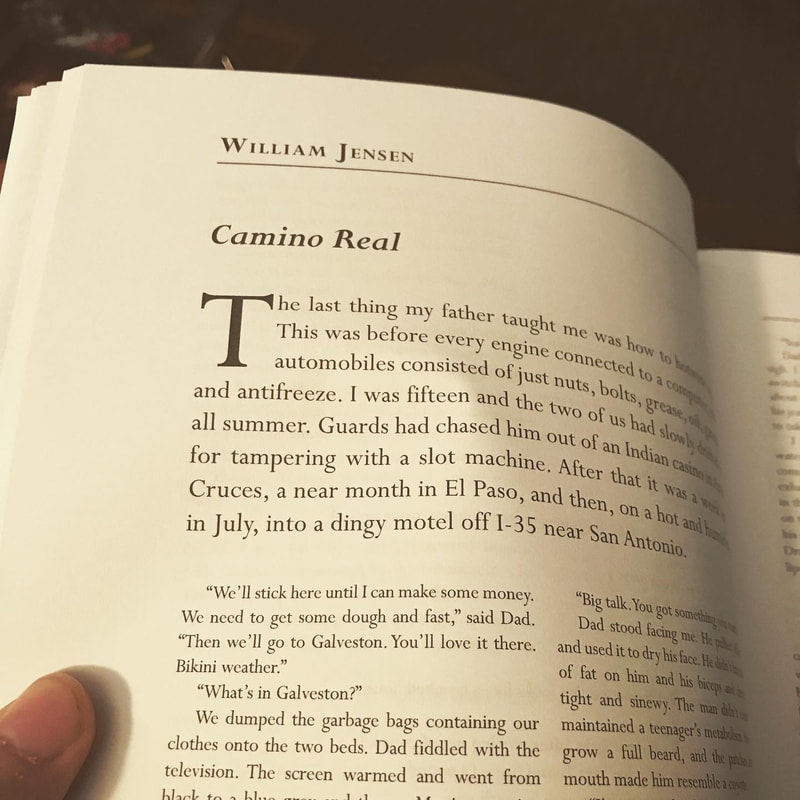

I had stories in Road Kill Vol.4 and Vol. 5. and now I'm getting a great opportunity to bring new Texas Terrors to y'all. Anyone who wants to submit can send me a story to [email protected] starting March 1st ! This is a paying anthology, and I really want to push the regional aspect, so be sure to have lots of whataburger and Lone Star beer! I love scary stories. I cannot wait to read yours!  Cowards and Cohorts The Fear of Everything: Stories by John McNally Lafayette: University of Louisiana at Lafayette Press, 2020. $20.00 172 pp. paperback. John McNally is one of those rare writers who might be considered a “writer’s writer” because his work is always structurally beautiful while his prose never draws attention to itself. He is in a tradition (mostly) of the mid-twentieth century American realism of Frank Conroy, John Cheever, and Richard Yates. But unlike those men, McNally’s characters are much more eccentric, humorous, and all around entertaining. His newest collection of stories, The Fear of Everything, celebrates the confusion and chaos of an uncomfortable world. The opening story, “The Magician,” is pure McNally. Set in the Chicago suburbs of the 1970s, McNally spins a classic coming-of-age narrative dealing with the disappearance of a young girl. But this is far from a police procedural and works more with ambiguity than with crime. Told in a collective voice of first-person plural, “The Magician” has small echoes of “A Rose for Emily,” and parts of The Virgin Suicides. A lesser writer might try to zero in on the tabloid aspect of a missing child, but McNally focuses on the turmoil of the boys at her school, which makes the narrative concentrate on mystery, uncertainty, and wonder. At one point, McNally writes, “We, on the other hand, became haunted and obsessed, meeting on the blacktop before school, huddling in the cafeteria during lunch, walking slowly home after the last bell rang, all the while going over what we knew and didn’t know.” McNally can summon the mindset of teens and young people better than most, and his focus on the boys’ anxiety muddled with angst and hormones is honest and gripping. The book’s title story switches gears as far as characters, but McNally’s trademark wit is consistent. “The Fear of Everything” focuses on a middle-aged man who has recently been widowed and is having a sort of mid-life crisis without harming himself along the way. The protagonist, Larry, shaves his head, grows a mustache, buys a sportscar, and eventually meets up with the curious Zoe, but Zoe is far from being a manic-pixie-dream-girl trope. She’s married and wants to swing. Her husband is described as “heavily bearded and eyebrowed.” On top of that, Zoe experiences pantophobia—or a fear of everything. This complicates things in unexpected ways reminiscent of the early stories of Ethan Canin. The arc of the story is simple but satisfying, and the themes of fear, love, memory, and forgiveness vibrate through the entire collection. However, my favorite story out of the nine would easily be “The Blueprint of Your Brain.” It is difficult to describe what makes this story so amazing without spoiling any of the wonderful twists, but at its core, “The Blueprint of Your Brain” is about a friendship between a boy and an old man. As the boy, Jimmy, learns more about his friend, he tries to emulate his older sense of style, swagger, and confidence. He begins wearing a hat and using slang from ’30s and ’40s. He wears blue Florsheim shoes. Though there are complications and reversals along the way, the journey is riveting. McNally keeps the tension and humor taut, but he also manages to create wonderful worlds where boys discover dangerous truths while old men reject ideas of redemption. Ultimately, McNally’s The Fear of Everything is wonderful collection in the tradition of T.C. Boyle. From the sidewalks of the Midwest to the isolated villages in the 1830s, McNally has captured a world all his own. I am positive any fan of short fiction will devour these humorous and haunting pieces.  I have meant to post this, but I am just now getting around to it. I have known for a while that Stoneboat was going to reprint my story "Camino Real" in their special 'decade' issue, but (understandably) they had some printing complications, so the edition didn't come out until this month. I received my contributor's copy while I was sick, so it was a nice surprise for me between naps, sneezing, and doping myself up on cold medicine. It is a fine looking publication, and I am super proud that they chose me to be a part of their 'best of the decade' edition. This story was nominated for a Pushcart Prize when it was first published in 2014. That seems like a lifetime ago. So much has changed. The 2010s had some ups and downs, but I like to think there were more high points than lows. In 2010, I was in grad school and submitting to journals and not sure what the future held. By 2015, I was being published fairly regularly, had graduated, become the editor of two literary journals, and had a completed novel manuscript. Now, in 2020, I have a literary agent, one novel in book stores, another novel being revised (draft 6?) and a confidence I never thought I'd have. It is easy for writers to get discouraged. It take so much time and energy to get anything on a page, let alone something that we're proud of--and today the page cannot compete with the screen. The glory era of publishing stories in the slicks is over. Most literary journals cannot even be found in book stores; heck, it's difficult even finding book stores! Celebrated writers are few and far between. The one percent of the one percent. It isn't difficult to lose focus, to abandon hindsight. I started the last decade without a single publication. Today I am being reprinted as one of the decade's best. I should never complain. I meant to upload this a while back, but here I am reading a little bit of my story "You Can Outrun The Devil if You Try." I hope you enjoy it! Anyone who knows me knows that I love everything that’s spooky. Horror movies, ghost stories, haunted houses, Tales From the Crypt comics, urban legends, and Halloween. I love all of it. But oddly, I’ve never written a straight up horror story. Until now.

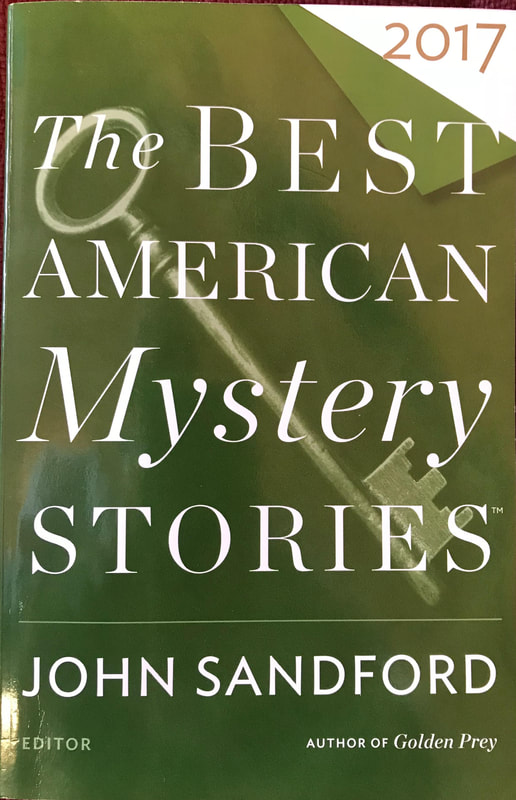

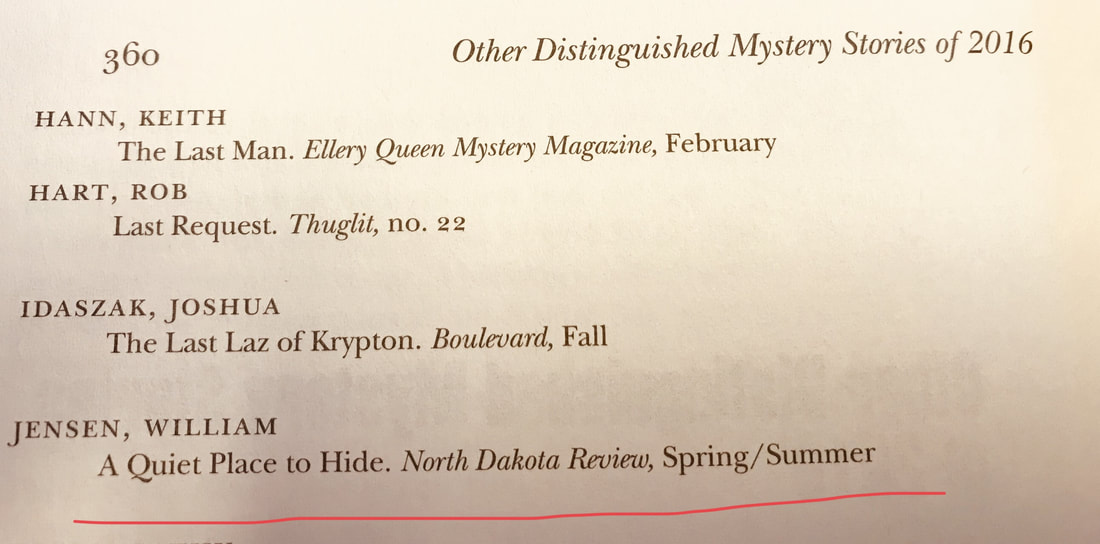

My short story “You Can Outrun the Devil if You Try” is in the anthology Road Kill: Texas Horror by Texas Writers vol. 4. And for me this is a big deal. I’ve had plenty of stories published, I’ve been in other anthologies, but trying to write something specifically “horror” was both difficult and freeing. I am not sure if I’ll honestly ever write another “pure” horror story again—maybe—but this was a blast to write, and I feel honored to be included in this beautiful anthology. Available now: So every year the Best American series comes out. These titles include Best American Sports Writing, Best American Short Stories, Best American Essays, and each anthology lives up to its name. They're big deals. It's not like a contest that anyone can enter, every year there is a new editor who makes an initial selection of publications from various journals and magazine, and then a new (smaller) list is made from the gathered titles. The first anthology came out in 1915. Many editions include big names such as Joyce Carol Oates, Benjamin Percy, Lorrie Moore, John Updike, Susan Sontag, Ron Carlson, and Raymond Carver.

On Friday I was writing early in the morning like I always do. On my desk was the 2017 Best American Mystery Stories, which I had bought months ago. I'm not sure what I was looking for or why I flipped it open, but the pages flipped to the back and I did a total triple-take. I saw my name. I saw my last name and my first name. My brain wasn't sure what was happening. Apparently my story "A Quiet Place to Hide" was noted as one of the 'Other Distinguished Mystery Stories of 2016' and no one had bothered to tell me! Obviously, receiving an honorable mention isn't the same as being included in the anthology but it sure felt like a great pat on the head. I just wish someone (somewhere) had told me! The darn book came out in October! You think someone I know would have noticed. What a thrill!  The morning came cool and blue and gray. Hawkeye and I sipped coffee and watched the giant rocks and hills growing pink and rosy. We’d slept well and had a lot of energy. The end was near. Because we’d taken a day to haul water from the river up the mountain, we knew we didn’t have enough time to hike to Apache Junction. We’d continue on for a day and then walk into town. From there we’d have to figure out a new plan. But until then we had to hike. We’d have to cross the highway and up another hill. And we’d have to find the cache that we hid in a small canyon almost a week ago. We packed up our tent and our bags as a soft mist floated over the desert. The terrain was flat and easy to navigate. Hawkeye led the way and we talked about women, books, and food—we were hungry and ready for a real meal. We’d been living off of cliff bars, oatmeal, and beef jerky. Now we wanted big juicy cheeseburgers, pancakes and bacon, ice cream sundaes drowning in hot fudge. And beer. Lots of beer. Buckets of ice cold American lager. We knew we’d eat well when we dragged ourselves into town. But until then we had to walk. And we had to cover a lot of ground. Hawkeye and I reached the highway early in the morning. We took a break to rub our feet, get a snack, fill our water bottles at the rest stop. I didn’t realize just how far we had to walk. I thought it was going to be an easy last day. Hike a few miles, be done by lunch, set up camp, and kick back and read some Louis L’Amour. I didn’t know what was ahead. On the western side of Highway 60 we passed through ruins of old cabins and brick lodges collapsed to ruble. Small graves were marked with crosses at the base of trees. We wandered through decayed and forgotten ranches and deeper into the Sonoran and into the hills. My feet were really starting to ache when we began to ascend. My feet had been killing me the whole trip. It didn’t help that the trail was all flint and jagged stone. Every step made me wince. I kept on. I followed Hawkeye and tried not to let on how much pain I was in. I started counting my steps and doing math in my head to figure out how much we had traveled. I calculated how long until we did a half mile. Then I’d start over and count again until a full mile was completed. It distracted me a little. But only a little. When we started to near the top, Hawkeye stopped and looked at his GPS. He began nodding to himself. His eyes rolled up the way he did when whenever he was thinking hard. I stood there panting. “We might as well set up camp relatively soon,” he said. He didn’t look at me. He stared down at the valley and the endless sprawl of Arizona. “Why? Why here?” I said. “Well,” he said, “pretty much from here on out we’ll be the same distance from the cache.” “Yeah?” “And since we’ll just have to backtrack tomorrow morning to get to town, we might as well stop, drop our bags, go find the cache without all our gear weighing us down, and come back for the evening.” “Makes sense,” I said. “How far away is the cache?” Now… here is where things get interesting. Apparently, Hawkeye said “0.8th of a mile.” But what I heard was: “An eighth of a mile.” “Yeah?” I said. “That’s nothing! Let’s go get it!” We stripped off our bags and began to wander off the trail and through the rough brush and cacti, careful not to step in cow shit, looking for snakes all the while. The decline was steep and difficult. I started to wonder how I’d haul my cache of goodies back up through the wilderness. We reached the dry river bed at the bottom and started moving north. “We should be getting close, right?” I said. “Nah,” said Hawkeye. “It feels like we should be there by now.” “Nah.” “What do you mean? How far do we have to go?” And that was when I realized how I misheard Hawkeye. We essentially had to march a rough mile through heavy sand, which took forever. And since we had to move under barbed wire fences and through cow pastures and around thorny bushes, we probably walked more like two miles. But finally we found the small canyon where we hid our food: granola bars, fruit cups, freeze dried meals, beef links, and gallons of water. We sat on the rocks and ate salami and canned peaches. Wind whistled through the canyon, and large birds floated in the distance. Hawkeye and I devoured our lunches without speaking. We knew we wanted real food. And a shower. And a bed. The adventure of the big hike was great, but we were getting ready to return to civilization. To our homes and our friends. The hike back to our bags wasn’t that bad. We found a trail so we didn’t have to scuttle through the wilderness again. The evening, our last one in the desert, was a relaxing one with the Arizona sunset living up to its reputation. Hawkeye and I perched barefoot on a boulder and drank black coffee and discussed what we would do tomorrow. We’d have to get into town. That was problem one. Then what? “We get food,” I said. “And then we start drinking. After that I don’t care.” “Okay,” said Hawkeye. “But we will need to get back to Phoenix to catch our flights.” “We’ll figure that over beer,” I said. “Fair enough.” The next morning we hiked back down the hill. We sang old Guns n Roses songs to keep our spirits high. We kept talking about how much beer we were going to drink. We started singing “99 Bottles of Beer,” and we actually finished the whole damn song, too. Going downhill wasn’t that bad. But then we returned to the highway, which we had to take into the small town of Superior. We had about four miles to go. Hawkeye wanted to run into the Boyce Thompson Arboretum, but I decided to sit by the side of the road, take my shoes off, and rub my feet instead. The hard blacktop was murder on my dogs. Finally we stepped into the city limits. We scanned for some place to eat. We didn’t care about quality or price. We just wanted food. We wandered into the Buckboard City Café like two old prospectors or wild men who’d been stranded in the wastelands. We took off our packs and collapsed at a table. I’m sure we smelled awful. A waitress appeared. “Water,” said Hawkeye. “Water,” I said. We ordered the biggest hamburgers they had. We devoured them in seconds. Then we ordered another round of cheeseburgers. I wanted apple pie for dessert, but they were out, so Hawkeye and I split a cinnamon bun and slurped down some room temperature coffee. The diner was nearly empty. Hawkeye noticed that there was a bar on the other side of the restaurant. He went and checked it out. When he returned he told me they’d open in about ten minutes. “Sounds good to me.” We paid our bill and drifted into the saloon. The bartender was a large man with a thick white beard. He said his name was Roy. We all shook hands and ordered our first round. Roy used to be the mayor of Superior and had lots of stories and was one of the kindest guys I’d met. Hawkeye and I sat outside and took off our shoes as we drank our beer. I saw a skinny guy in short-shorts marching toward us. He had a big ’70s style mustache and wore sunglasses that shined like jewels. He carried a heavy backpack on his shoulders. When he got close to us he asked if we’d been on the Arizona Trail. We said we had. He smiled, took off his pack, pulled out a pack of Marlboro Reds and lit on. He’d just gotten off the trail himself. He’d been hiking all the way from the Mexico border but had to get back to Iowa tomorrow for work. He said his name was Taylor but his trail name was Slug. Taylor joined us for the rest of the night as we drank beer and listened to Roy tell us all about Superior’s history and his youth growing up in the town, how the place had changed. A tamale festival was going on, so the one hotel was booked, but Roy said we could set up our tents in the back, and that’s exactly what we did after we got our fill of Budweiser and IPAs. Other folks started coming in. Miners and cowboys. All friendly and eager to buy us a round, glad to hear how much of the trail we’d hiked. It almost felt like we’d been coming to that bar all our lives. In the morning we crawled out of our tents and returned to the Buckboard City Café to get breakfast. Hawkeye fiddled with his iPad to secure us bus tickets back to Phoenix. Taylor had a buddy coming to pick him up. Hawkeye and I got a photo with Taylor before we went our separate ways. But as we stood on the corner waiting for the bus, an SUV sped by and Taylor stuck his head out the window and screamed “Adios, my friends!” And that’s where I want to end this. I could tell you about the bus ride back to Phoenix, our navigation downtown, our search for hotel, the dinner of Thai food, and how Hawkeye was finally able to Facetime his wife and son again. But all of this is really about two friends hiking around the Superstition Mountains in Arizona, two guys out in the rough desert away from people, technology, and everything. To write about our return might not dilute any of that, but I feel the adventure ends in Superior. That’s where we stopped walking. That’s where we left the trail. That’s where we concluded our big hike.  Hawkeye and I rose early the next morning. Our legs stiff with the desert’s chill and the previous day’s descent and climb. In the dark we fixed our oatmeal and our coffee. We stared in hard silence at the licks of blue flame from the stove while we waited for the water to boil. Dawn came over the mountains as we pulled on our packs. Though our limbs ached, our feet throbbed, we also felt rejuvenated and confident. We had water, plenty of water, at least for the day. And we knew we were close to the pinnacle of the week’s climb. Once we reached the top it would (mostly) be downhill. And it was easily the best day of the trip. At least for me. We climbed to the crest fairly easily and soon. The sky still had some streaks of plum and nectarines in the horizon, and the air was still cool and fresh with the sunrise. Looking out and across the desert lay a land untouched by man. The cliffs and the rocks rose out of the ground as twisted statues of forgotten and lonesome gods. We walked slowly and tried to breathe it all in. It wouldn’t be long before we’d be on a plane and back to our respected lives and jobs and all of it would just be memories. We didn't talk about it. But we knew we were both trying to remember every detail as best we could. The cacti, the rocks, the sapphire sky without end, even the pain in our feet. We found ourselves stopping a lot and gazing at the distance and listening to the silence, maybe the wind through the valley and nothing more. The day grew warm. We had several miles to go until we reached the next water spot, which was a water cache where people left jugs of water—some for themselves to find later, some donated by other hikers for people like Hawkeye and myself. I didn’t tell Hawkeye, but about two miles out I was out of water. I knew I would be okay, but I felt embarrassed for consuming it all after we’d gone through the dangers and the hassle of collecting water just the other day. My feet were killing me, but I tried to move quickly. I figured it was best to get to the water cache as soon as we could. When we crossed over the dry river bed and saw the brown iron box, we hesitated before opening the door. I think we were both afraid that we might open it to find it empty and then we’d be in trouble. But the cache was fully stocked with gallons and gallons of precious H2O. Hawkeye and I hugged each other in exhaustion. We set up a little shelter using a tarp to shade us from the sun and refilled our camelbacks. For lunch that day we ate beef jerky, salami, dried fruit, peanut butter on tortillas, and cliff bars. I took off my boots and let my feet breathe. As we sat there about five people came by on horseback. We said hello and they decided they’d have lunch there, too. One gentleman approached us and asked us what was with the iron box. “It’s water cache,” said Hawkeye. “People put jugs of water in there for anyone who comes along.” “You mean like Mexicans?” Hawkeye and I glanced at each other. “More like hikers like us probably.” “Are you guys packing?” Hawkeye and I noticed he had a snubbed nose .38 strapped to his hip. Having grown up in Arizona I was used to seeing people open carry, but I think Hawkeye was a little confused. “Nah,” I said. “Oh, man, I wouldn’t be out here without a firearm. You don’t know who you’ll run into.” The man started to tell us how undocumented workers wandered through the Tonto National Forrest on their journey from Mexico to Phoenix, but I stopped listening. I had met plenty of guys like him before. He had a thick New Jersey accent. He was riding a horse out in the desert without a hat. “Where are you guys riding from?” I said trying to change the subject. I wasn’t sure how close we were to Apache Junction, but we’d encountered other horseback riders from there. He shot me a look with a shrug. “From the parking lot! Where else? Idiot.” “Ah,” I said. When he and the others got back on their horses and rode away, we all waved and wished them well. As soon as they were out of sight I turned to Hawkeye and said, “Well, that guy sure was an asshole,” and we broke out laughing. TO BE CONTINUED It was just after New Years that my buddy David “Hawkeye” Latham called me up and asked if I wanted to do a big backpacking trip. He’d been reading about the trails in Arizona, which is where I’m from. He said he wanted to see some saguaros with their arms stretched out like they were being robbed. January was shaping up to be a bad month, and I was losing my mind a bit. I needed something to look forward to. I needed to get away. I needed an adventure to shake me up. I was more than ready to hike back into the desert.

It took some planning. Lots of e-mails and phone calls. Lots of lists. But in mid-March we met up in Phoenix and headed east toward the Superstition Mountains. Having grown up in the Grand Canyon State, I knew that those mountains had a lot of bad mojo—lots of folks died in those hills. Some people went missing looking for treasure, others claimed to have seen giant Lizard People. Most of the men and women who never came back alive were the hikers who tried to walk across the desert in July and August with little water. Anyone who has read Urrea’s The Devil’s Highway will tell you that’s a bad idea. But March was wonderful for hiking the hills and valleys of the Sonoran desert. Never too hot, never too cold, and with a bit of color in the cactus flowers and a faint mist in the mornings. Our first few days went wonderfully. It stayed overcast and sprinkled a bit as we trekked in the mornings. We were miles away from everything. We followed the Gila River for miles before turning north and into the Tonto National Forrest where we wandered by steep cliffs and rugged paths of stone and sand. My legs and back were strong. David and I carried probably between forty and fifty pounds on our backs—maybe more. We aimed for roughly ten miles a day and kept a moderate pace. But it wasn’t long before my feet were killing me. I didn’t know my feet could hurt that bad. And then, as if being alone in the desert wasn’t enough, we ran into our one fear: We ran out of water. We’d finished the day’s hike without coming across any of the water spots on the map—or those spots had been dry as a barrel of dust. Latham and I sat down on the narrow trail and looked out across the valley and the scarred mountains around us. We caught our breath and talked out the scenario. We could abandon ship. We could try to press on and hope for the best, which was the most risky option. But Goonies never say die. We waited until dark. We got a little sleep but then, at 2:00 AM, we got up, emptied our packs in the brush by the trail and descended five miles back toward the Gila River. We took our Camelbacks and anything that might be able to hold water. Plastic bags, bottles, jugs, and cans. A person can go days without food. Water was more important. It wasn’t too bad a walk. It was cool in the early morning, our packs were now super light, and we were going downhill. We made it back to the river by the dawn. It took us a while to fill up everything. One of our water pumps broke on day one. But we were not in any rush. We sat by the cold rushing stream and filled everything we had with precious H2O. We rested and ate a simple breakfast of tortillas and dry salami. By the time we returned to our stuff at the top of the mountain we were exhausted from lack of sleep, adrenaline, and pushing ourselves to retreat and return through the desert. But we’d done it. We had plenty of water. That night we ate our freeze dried dinners and treated ourselves to scalding black coffee for desert. We slept under the stars ready for the gravy of the next day. TO BE CONTINUED |

Archives

September 2022

William JensenWriter living in Central Texas. Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed